The unique “Spiderweb” special operation carried out by Ukraine’s Security Service (SBU), which resulted in drone strikes damaging 41 Russian aircraft, has drawn significant attention abroad. In the U.S., it has sparked renewed debate over the need to invest in more robust aircraft shelters and reinforced infrastructure at airbases. The scale of the operation and the damage inflicted highlight the growing threat posed by drones in modern warfare.

As part of Operation “Spiderweb,” Ukraine deployed around 120 kamikaze drones to strike multiple airfields, aiming to destroy or heavily damage 41 Russian military aircraft. According to Andriy Kovalenko, a representative of Ukraine’s National Security and Defense Council, “at least 13 Russian aircraft were destroyed.”

Photos from the aftermath suggest a critical vulnerability exploited by the Ukrainian drone strikes: Russian aircraft were positioned in open areas on exposed runways. The scale and coordination of the attack allowed a large number of planes to be disabled before they could take off.

Last year, Russian Defense Minister Andrey Belousov stated that a construction schedule for new airfields had been approved and that protective shelters would “definitely be built” in response to Ukrainian missile and drone attacks. While some construction has taken place, it has primarily been focused on airbases located closer to the Ukrainian border.

Russia’s construction of new aircraft shelters reflects a broader trend seen in other countries. While the U.S. military already has shelters at various bases, investment in new hardened infrastructure significantly declined after the Cold War. Proposals to build additional shelters have often lacked political or financial support, given the high costs and competing priorities – such as funding active defense systems or expanding the number of forward-operating bases.

At the same time, concerns are growing that U.S. forces are increasingly vulnerable, particularly to drone attacks, due to the lack of investment in hardened shelters and fortifications. A recent deployment of six U.S. Air Force B-2 stealth bombers to Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean has added fuel to this debate. The island has only four shelters designated for B-2s, none of which are reinforced, leaving the bombers parked in the open.

“While air and missile defense systems are an important part of protecting bases and forces, their high cost and limited availability mean the U.S. cannot deploy them widely enough to fully defend all our installations,” wrote a group of 13 members of Congress. “To complement active defenses and strengthen our bases, we must invest in passive protection measures such as hardened aircraft shelters, underground bunkers, and force dispersion.”

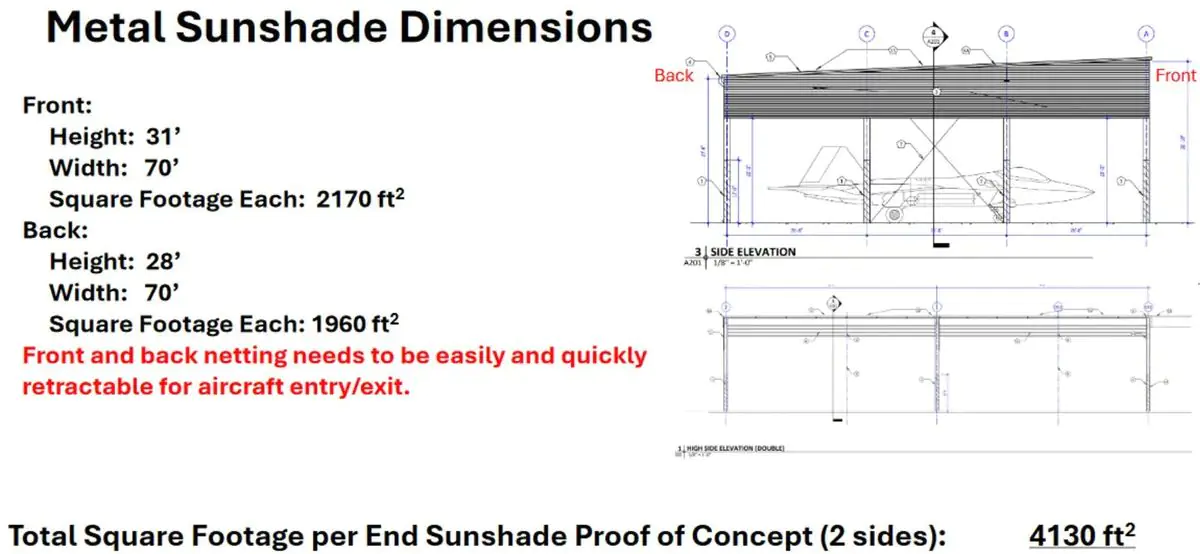

They note that while reinforced aircraft shelters do not offer complete protection against missile strikes, they provide significantly more defense than temporary structures. Even fully enclosed, but non-reinforced shelters can offer limited additional protection against drone attacks. Last year, officials at two U.S. air bases expressed interest in adding netting or similar physical barriers to existing open shelters to guard against small drone threats. Both Ukraine and Russia are now using such nets to shield aircraft.

Although Ukraine stated that the planning, preparation, and execution of the unprecedented Operation “Spiderweb” took more than a year and a half, the main barriers to conducting drone attacks remain relatively low in terms of cost and technical capability. The operation employed ArduPilot, described as an “open-source autopilot system” that is publicly available online.

Over time, drone threats will only grow more complex, largely due to advances in AI. Ukraine’s attack underscores that these threats are not limited by distance or borders. An adversary can launch unmanned aerial vehicles from 1,000 miles away, from an area near the target, or from any point in between – whether from land, sea-based platforms, or airborne systems.

Despite this, the U.S. military still lags in implementing counter-drone measures for forward-deployed forces, as well as for domestic bases and other installations. Within the U.S., progress is further hindered by a complex web of legal, regulatory, and other constraints.

Source: twz