I’m willing to bet that many of my readers are fans of one of the iconic American combat aircraft – the A-10 Thunderbolt II attack jet. However, the emergence of this Cold War symbol was preceded by a long history of technical and tactical development. It’s worth noting that U.S. attack aviation recently celebrated its 100th anniversary.

TABLE OF CONTENT:

First steps

The official birthdate of U.S. attack aviation is considered to be September 15, 1921, when the First Reconnaissance Group was reorganized into the Third Attack Group. It was based at Kelly Field, near Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas. Initially, the unit operated Salmson 2A2 reconnaissance aircraft, but after the role change, the group was re-equipped with De Havilland DH-4B planes. While the DH-4B was a decent light bomber for its time, it didn’t fully meet the requirements for an attack aircraft – mainly due to the complete lack of armor protection. The Army Air Service needed a new plane in this class.

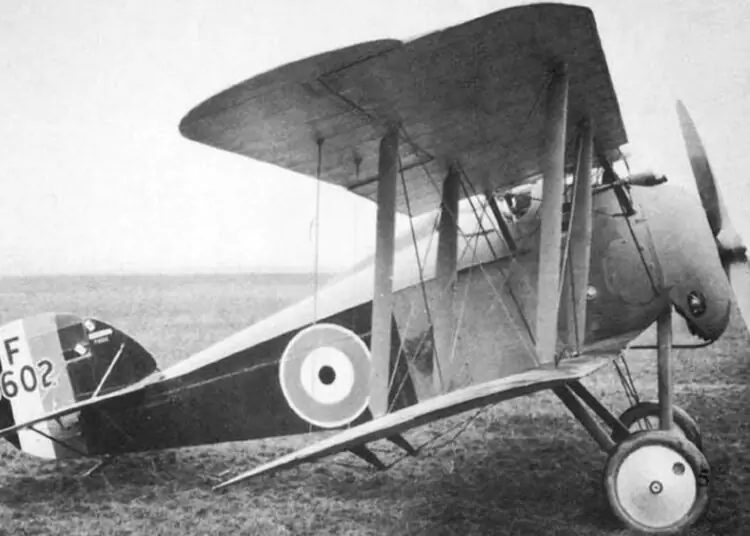

The inspiration came from the British Sopwith TF.2 Salamander – a armored version of the well-known Snipe fighter, designed for direct infantry support on the battlefield (TF stands for “trench fighter”). One Salamander was brought to the U.S. in early 1919 and tested at McCook Field Airbase in Ohio.

The results didn’t fully satisfy the U.S. military. They believed that an aircraft intended for direct ground support needed much heavier armament, including machine guns and cannons, whereas the Salamander, like the Snipe, was equipped with only two synchronized machine guns.

Requirements for such a plane were published on October 15, 1919. Given the complexity of developing a fundamentally new attack aircraft, the military hesitated to assign the task to civilian companies. Instead, the Engineering Division of the U.S. Army Air Service, based at McCook Field, took on the project.

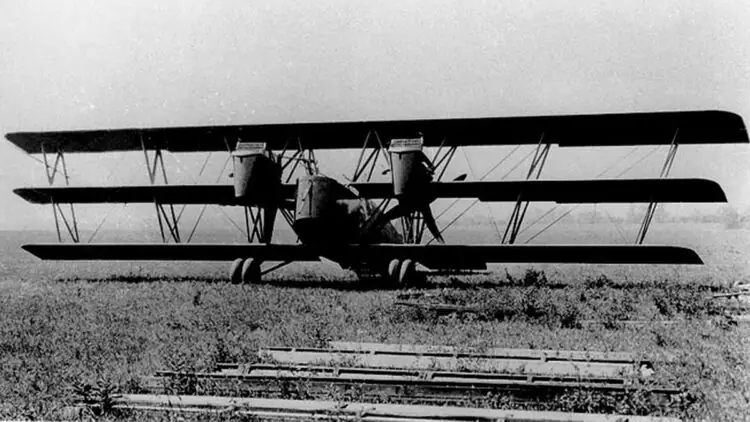

GA-1

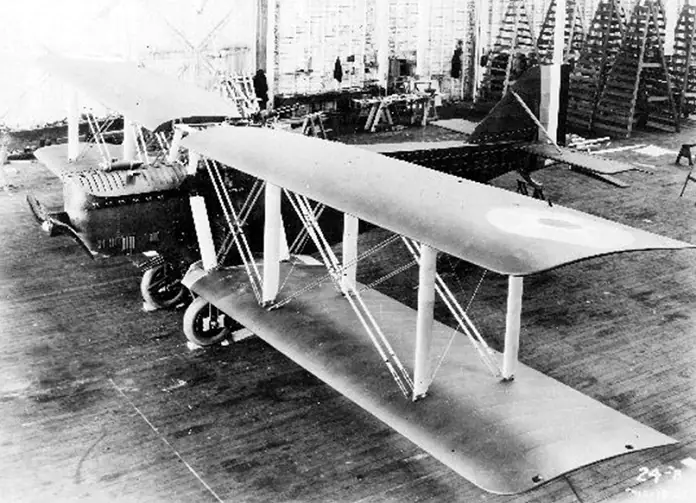

The result of the efforts led by military engineer Isaac M. Laddon was an imposing machine – a twin-engine triplane with engine nacelles mounted on the middle wing. The engines were standard 12-cylinder Liberty units used by the U.S. Army Air Service at the time, equipped with pusher propellers. The prototype was designated GAX – Ground Attack, Experimental – although pilots often interpreted the first two letters as “Guns, Armor.”

According to the attack aviation concept of the period, the GAX’s armament was exclusively firearms and cannons – no bombs were included. The aircraft carried a 37mm Baldwin cannon mounted in the nose gun position, along with eight 7.62mm Browning machine guns. Four of these were fixed in the front fuselage, firing forward and slightly downward. The remaining guns were placed in defensive mounts: one in the forward cockpit firing backward and upward, and three in the rear cockpit – one covering the upper hemisphere and two covering the lower hemisphere, with the latter firing through a tunnel in the fuselage.

The airframe was entirely wooden, covered with fabric and plywood. The fuselage had a rectangular cross-section. The upper wing had a larger wingspan compared to the middle and lower wings. Ailerons were installed on the middle and lower wings.

The GAX’s crew consisted of three members: a pilot and two gunners.

Armor protection was made from 4.75 mm (3/16 inch) thick plates, shielding both the crew and the engines. Out of the aircraft’s 3.5-ton empty weight, nearly one ton was armor.

The GAX prototype, assigned the military number 63272, was built at the workshops of McCook Field. Development moved quickly, and the aircraft made its maiden flight on April 3, 1920. Pilot Harold R. Harris noted poor handling, significant vibration, and noise. Despite these issues, the military placed an order for 20 production units on June 7.

Since the McCook Field workshops couldn’t meet the demand, the contract was awarded to Boeing. The aircraft received the company designation “Model 10,” and once adopted by the military, it was assigned the index GA-1. The production models were largely similar to the prototype but replaced the Baldwin cannon with a 37mm Puteaux SA 18 gun. There was also an option to remove some machine guns and install mounts for fragmentation bombs weighing up to 250 pounds (113 kg).

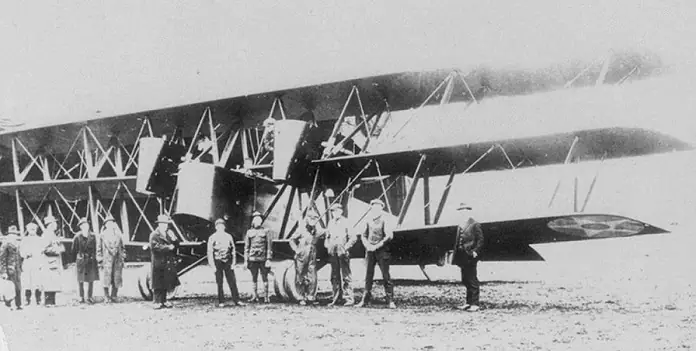

Deliveries of the production GA-1 models began in May 1921. However, the original order was cut in half due to limited military funding at the time. The serial GA-1s were assigned military numbers 64146–64155, with factory numbers 200–209.

Thorough testing of the production aircraft revealed several issues: poor cockpit visibility, low thrust-to-weight ratio and climb rate, limited flight range, and an inefficient cooling system that caused engine overheating. Some of these problems were fixable, while others were not critical for an attack aircraft.

The most significant drawback was poor maneuverability, which made aiming difficult. Additionally, heavy vibration in the aircraft complicated precise targeting.

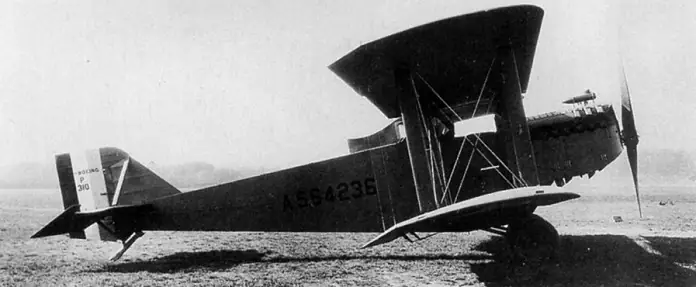

GA-2

An alternative to the twin-engine GA-1 was the single-engine GA-2 attack aircraft, also designed by Isaac Laddon. This model was a biplane and significantly more aerodynamically refined. The crew of three was protected by an armored box made from 6.35 mm (1/4 inch) thick plates that shielded the engine and cockpit. This armored section was an integral part of the fuselage. The rest of the fuselage and wing structure was wooden, covered with fabric and plywood.

Due to the aircraft’s heavy weight, a powerful engine was needed. Since no suitable engine existed at the time, the Engineering Division took on its development. The resulting liquid-cooled powerplant delivered 750 horsepower and featured 18 cylinders arranged in three banks, forming a W-shaped configuration.

The GA-2’s armament was only slightly different from its predecessor’s: it carried a 37mm cannon and six 7.62mm machine guns. The cannon and two forward-downward firing machine guns were mounted under the engine and operated by the front gunner. This gunner also controlled two machine guns firing backward and downward. The remaining pair of machine guns was mounted on a top turret, operated by the second gunner. Additionally, the aircraft was designed to carry up to ten 20-pound (9.1 kg) high-explosive bombs suspended under the wings.

On December 20, 1920, Boeing received an order for three GA-2 aircraft. Interestingly, like the GA-1, these planes were also designated as “Model 10” by the company.

Ultimately, the order for the third aircraft was canceled, and only two GA-2s were built, assigned military numbers 64235 and 64236, with factory numbers 310 and 311. The first was produced in 1921 based on Engineering Division blueprints. Its construction ran concurrently with engine development. When the engine was completed, it turned out it didn’t fit in the allocated space within the armored fuselage, requiring significant redesign of that section. As a result, the GA-2’s first flight took place only on December 18, 1921.

Construction of the second aircraft was delayed until the initial flight test results were available, after which Boeing made some design modifications. Overall, the GA-2’s test results were as disappointing as those of the GA-1. The GA-2 never entered operational service and was scrapped between 1924 and 1926.

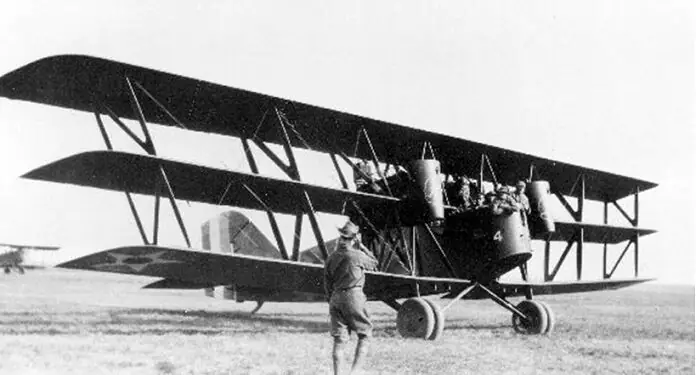

The completed GA-1 aircraft were transferred to Kelly Field and assigned to the 90th Squadron of the 3rd Attack Group. Initially, only one plane was assembled and used occasionally for training flights. However, by the end of 1922, several more attack aircraft were put into active service.

On February 9, 1923, three GA-1 aircraft, along with several DH-4Bs, took part in training exercises near the Mexican border, simulating an attack on a convoy. The exercises concluded that, under real conditions, the convoy would likely have been destroyed. At the same time, General Billy Mitchell proposed using the GA-1 as a form of airborne infantry. His concept involved equipping the planes with quick-release machine gun mounts. In combat, the aircraft would land behind enemy lines, allowing crews to disembark, set up defensive positions with machine guns, and hold their ground until infantry reinforcements arrived. Naturally, this idea was not well received by the pilots. Despite the skepticism, the GA-1 aircraft were modified to accommodate Mitchell’s concept.

The GA-1 aircraft remained assigned to the 3rd Attack Group but were rarely flown. Command used them as a disciplinary tool for young pilots who broke flight rules – threatening reassignment to GA-1s was usually enough to keep “airspace troublemakers” in line. At one point, Mexico showed interest in acquiring GA-1s for use against insurgents. American General Mason Patrick, involved in the negotiations, valued a single aircraft at \$15,000. However, the deal never materialized. Finally, in April 1926, the GA-1 was officially retired. This was met with relief among the pilots of the 3rd Attack Group.

Indeed, the GA-1 and GA-2 were far from the only attempts by American designers in the early 1920s to develop an attack aircraft. Several other unique models were built during this period. Those will be covered in the next part of the series.

Read also: